Day One at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens

It’s February 24, 2020, and the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST) in Athens has just opened its doors for the first time. We’re inside along with the museum’s first-ever visitors—kids from the 1st Experimental School of Athens, Plaka—and the museum’s curators, art conservators, management, and staff.

There’s no better way to spend a whole Monday than in a museum, particularly on that museum’s very first day, touring it with artists whose work is shown like Pantelis Xagoraris, Tsoclis, Rena Papaspyrou, and Ilias Papailiakis.

The museum’s path to this opening was a tortuous one, but what matters is that it is now open—and not just open, but vibrantly alive. The collection, with the help of the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF), has at last arrived in a home worthy of it, and the museum’s heart has started beating.

We have visited the museum dozens of times to follow the evolution of the project as supporters, but this is the first time we’re here as visitors, and it’s as visitors that we experience it.

Going up from the ground floor to the 4th floor of the collection, you feel uplifted, both literally and metaphorically. Join us for the ascent and experience EMST’s first day.

GROUND FLOOR

There are signs everywhere that the museum is alive. Words are flashing on a screen, in Greek: “BEEF IS ART. VODKA IS ART. BEEFEATER IS ART.” You stand still and stare at the screen. You close your eyes, open them again: “ART IS EVERYTHING AND EVERYWHERE,” by Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries.

The escalators go up and down. The building is breathing. People are moving up and down the different levels. Snapshots of Athens are framed through openings in the museum’s structure. A piece of Athenian sky, neoclassical buildings, some modern, contemporary, some abandoned, and others renovated. Your thoughts return to the ground floor and to Young-Hae Chang: “EVERYTHING IS ART.”

The building itself is the work of one of the most important representatives of post-war modernism in Greece, architect Takis Zenetos.

2nd FLOOR

The exhibition of the permanent collection begins on the second floor, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Hall. What will you see? Are you going to like it? What if you’re disappointed? You feel anxious—the suspense of a first encounter.

The first piece from the collection is audible before it is visible. Buzzing, crackling sounds lead you to Fix It by Mona Hatoum, a site-specific installation that uses parts and objects from the old Fix brewery, the formerly industrial building that now houses EMST. A part of the factory lives on here, with electric lamps that flash on and off and heat up. You feel a little tight in the stomach. You are walking at the slow pace lovingly dictated by museum environments.

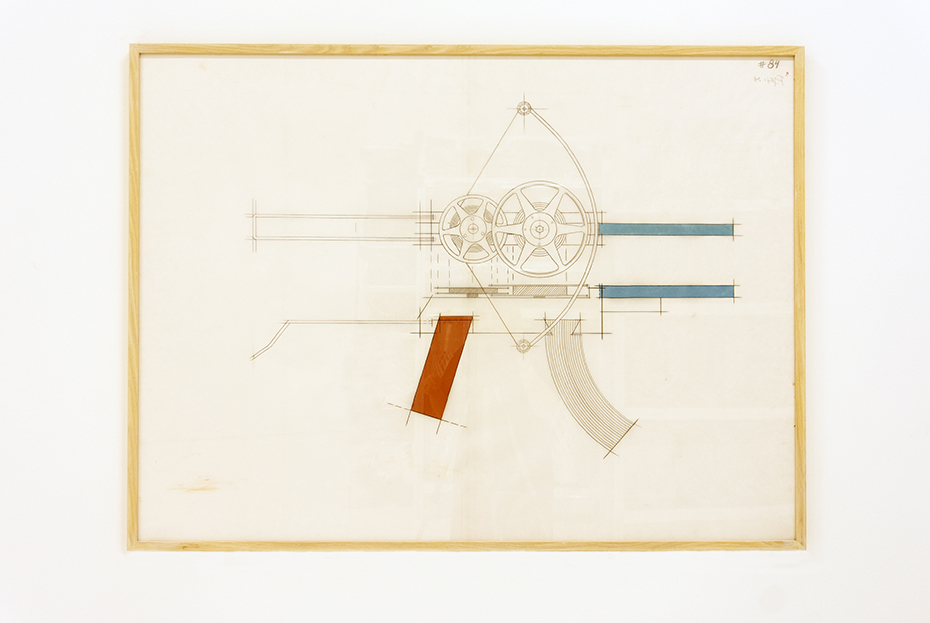

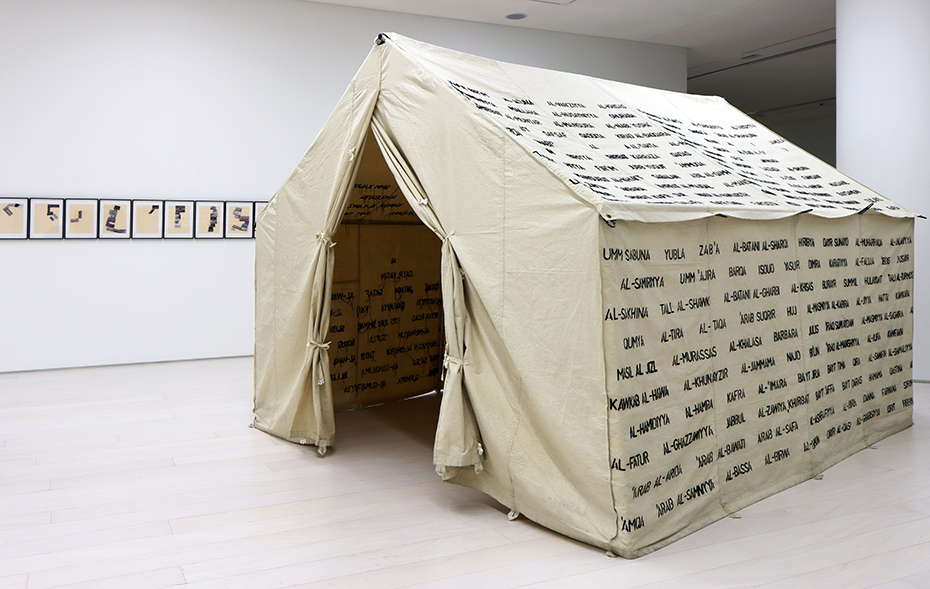

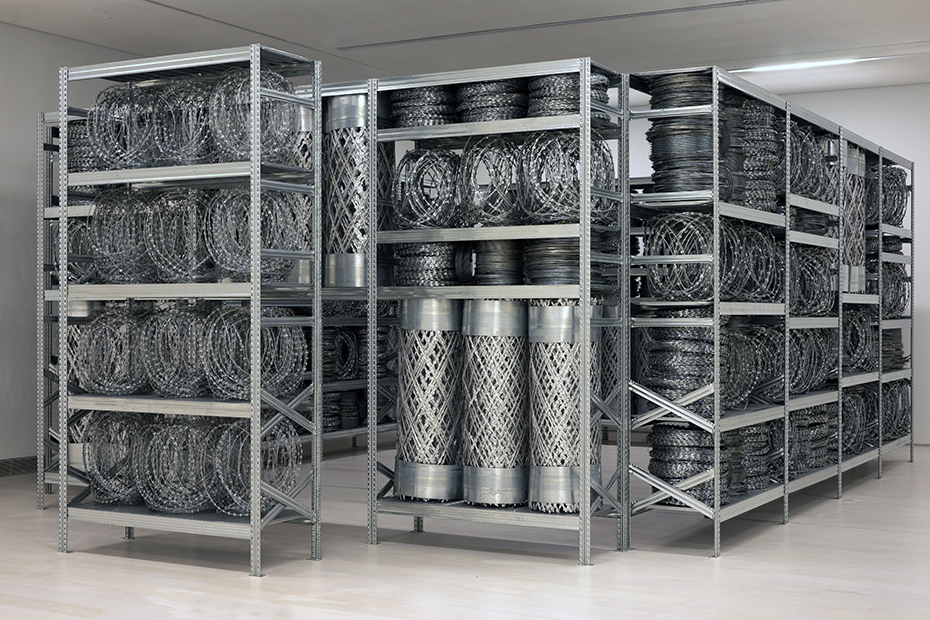

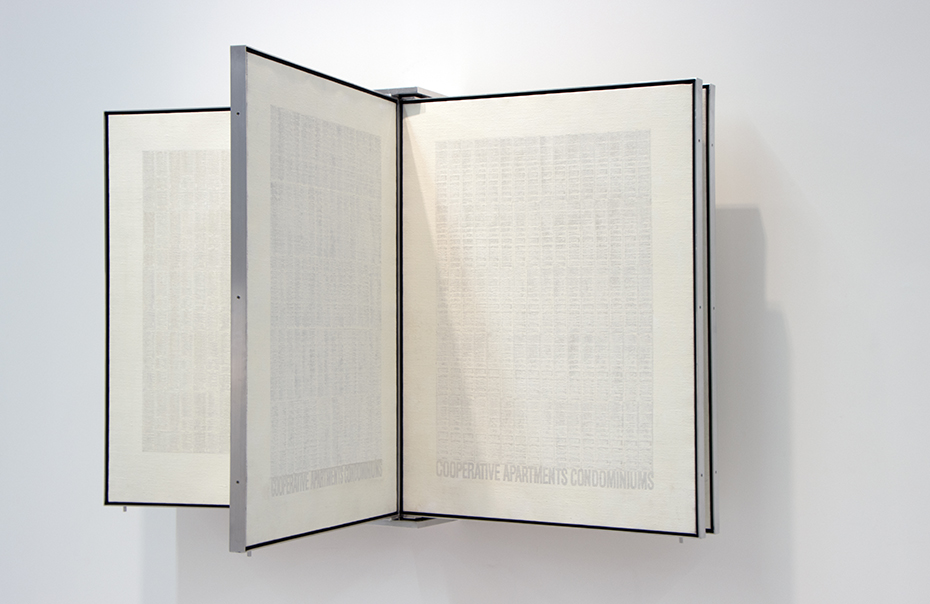

You see paintings next to installations, photographs, sculptures, and video works. Greek artists next to international artists. The anonymous figures in Vlassis Caniaris’ Hopscotch across from No Olvidado by American artist Andrea Bowers, a paper installation including hundreds of names as a tribute to those who have died crossing the border between the United States and Mexico. Works from the 1960s next to works from the 2010s.

There is a constant movement between the past and the present, the local and the international, acrylic paints and digital art. Without strict and specific themes, the works are loosely bound together, remaining open to our individual interpretations.

3rd FLOOR

You ascend the stairs to the 3rd floor and take a last look, from above, at the imposing installation by Jannis Kounellis. People are standing in front of the works, in a mental dialogue with the artists behind them.

You walk through a narrow corridor, a dividing line between seven pairs of photographs by Danae Stratou. An artistic interpretation of the border separating Mexico from the United States, the Green Line in Nicosia, the West Bank wall in Palestine. You notice that Danae Stratou is walking behind you.

All of the works have something to tell you. But some of them have a real voice. Actual words can be heard from one room, with pauses in between. “Will. There. Be. A. Moment. Of. Recognition?” wonders Gary Hill. From another room, you can hear a cover of “All by Myself” from the homonymous work by Nan Goldin. The museum takes you by the hand and guides you through the artists’ sounds and images. It activates your senses. Eyes and ears are fully engaged. A sign reads “Don’t Touch” in front of Tsoclis’ work The Wayfarer (Οδοιπόρος).

Tsoclis is with us on the day of the tour. He sees his work displayed and asks to make an intervention. Today’s technology is different from what was used at the time the work was created in 1989. Analog technology has become digital. His work, which comprises a partially painted canvas combined with a video projection, was originally placed in a dark room. Now, it is placed in a very brightly lit corridor. Two days after the museum opening, after the artists’ tour, Tsoclis revisits the museum with his brushes, and adds a bit more gray to the canvas where the screening is projected, 31 years after he created the work.

4th FLOOR

Our tour ends on the top floor of the collection with a few other very powerful works.

A wooden fence is visible towards the end of the exhibition. You look through the slats, and you see a large wooden boat. The artist is the innovative Ilya Kabakov. You learn from the curators that this is the largest piece in the exhibition. Everyone has questions, including the artists—artistic questions, but also practical ones. How was it set up? A special area was designed for the installation, and a structural design plan was carried out to remove a column and place it there, they inform you. The boat had been dismantled for storage. A special boat craftsman came to assist with the assembly, with the help of a video tutorial from previous installations of the artwork. The Russian artist could not travel, so his wife and art partner undertook the task, along with their daughter, of placing the twenty-five boxes on the deck, representing memories of the artist’s life to date. All of the small items and clothes were placed one by one by his daughter who traveled to Athens, under the guidance of her mother via skype.

These are just a few of the stories behind the 78 works from the collection exhibited in the museum. They’re live works that are still changing, like the museum, like all of us, and like the city around us.

You can’t help but feel that the museum is alive, and when you leave, you feel more alive yourself.

Completion of the works necessary for the National Museum of Contemporary Art to realize its fullest potential was made possible by a grant of €3,000,000 from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF). This grant helped the Museum outfit its exhibition spaces and prepare and transport its permanent collection. SNF supported the procurement of essential equipment and contributed to the establishment and upgrade of various Museum spaces, including the Media Lounge, the Conservation Laboratory, the Library and Artistic Archive, and the Screening Room.